“Getting to product/market fit AND being differentiated — that’s what’s hard.”

The term “growth hacker” first gained momentum in 2013. Back then, it might have seemed like a fad; now it’s ubiquitous in Silicon Valley. But what does it really mean to “hack” growth — and can you do it sustainably?

Andrew Chen, a member of the growth team at Uber in San Francisco, wrote an essay a few years ago titled, “Growth Hacker is the new VP of Marketing,” in which he built on the philosophy of Sean Ellis, GrowthHackers CEO, who first coined the phrase. “He was really a performance marketer,” says Chen. “Not only had he mastered that but he had gone even further down into actually tweaking the products, really thinking about features and getting deeply into product management.” Growth hacking means applying the problem-solving mentality of the engineering world to marketing, and the metrics-driven approach of the marketing world to engineering.

Chen has been described as an “elder statesman” in this still-nascent field. He has deep insights into how early-stage startups can start thinking about their growth engines, and intimately understands the cross-functional role that growth teams play. We recently welcomed him to our San Francisco location for a fireside chat as part of our “The Drunken Walk” series.

“So much of it ends up being about product/market fit.”

After studying Applied Math at the University of Washington, and precociously graduating aged 19, Andrew Chen went to work at the Seattle branch of Sand Hill Road venture capital firm Mohr Davidow Ventures. He was wowed: “Watching people pitch how they’re going to change the world — it was an amazing experience.” Then he joined one of their portfolio companies, in ad-tech, where he worked to unify human psychology and motivations with big data and engineering. Large and small, from dating websites to Myspace, the startup’s customers were all looking to advertising to help them scale. At the time, the term “growth” didn’t have the significance it does today, and growth teams didn’t exist. But Chen was already developing a deep understanding of a core principle: how to use optimization and metrics to inform great product design.

When he first moved to the San Francisco Bay Area about ten years ago, he was surprised at how many entrepreneurs were “like mini Steve Jobs”, espousing the “if you build it, they will come” mentality, and not thinking much about optimizing user acquisition. Quite often their intuition was enough, certainly enough to satisfy investors: “They would just say, oh you have like 200,000 registered users. That’s pretty good.” Not so nowadays. In 2007, the greatest challenge was the code. Today, Chen says, technology is not the limiting factor in a company’s success — the greatest challenge is finding product/market fit, having a product that’s differentiated from the competition, and mastering advanced traction metrics such as churn and retention.

“We have this interesting intersection of these super platforms like Google Play and the App Store and Facebook and all these things where you can actually go from zero to, let’s say, 10 million users in the consumer world in the blink of an eye,” he says. “I think it’s better because now we’re not chasing “flash in the pan” ideas.” With such a saturated market for apps, growth has to be part of the plan from the get-go: “We’re well into, I think, two million mobile apps, so we’re now in this era where you need to check all these boxes for it to work.” Plus ça change.

“What you’re talking about is not a growth hacker but a growth team.” (They’re different.)

To meet the need to improve advanced traction metrics, a lot of large companies — the LinkedIns and Facebooks of this world — have dedicated growth teams composed of engineers, data scientists, product managers, designers, and marketers. These teams have a very “quantitative mindset” and are focused on making tweaks to the product, such as adding viral features, and creating feedback loops that establish sustained growth.

Chen says that there are two schools of thought about the right time for a company to bring on a dedicated growth team. Traditionally, big tech players have waited until they have several hundred employees and millions of customers before allocating “a single owner for all these growth questions.”

But he says many startups that he sees today have co-founders building the growth team into the product team from day 1. And this is a different approach. These founders have a growth hacker mentality, which “requires a central insight about something that’s happening in the market in order for it to work” — if they’re in VR or AR, for example, maybe they’ve found a way to take advantage of a distribution channel for their content that no one else has thought of yet. “You need to have some ideas around distribution built in from the very beginning,” says Chen, who doesn’t believe in shortcuts or tips and tricks. “What you need is a system for growth — you need to think about it holistically.” (And of course no system is going to work without a great product, because “growth is a magnifying glass” — a diamond becomes a bigger diamond, a piece of shit becomes…shittier.)

“Do something quickly to validate that it even works at all.”

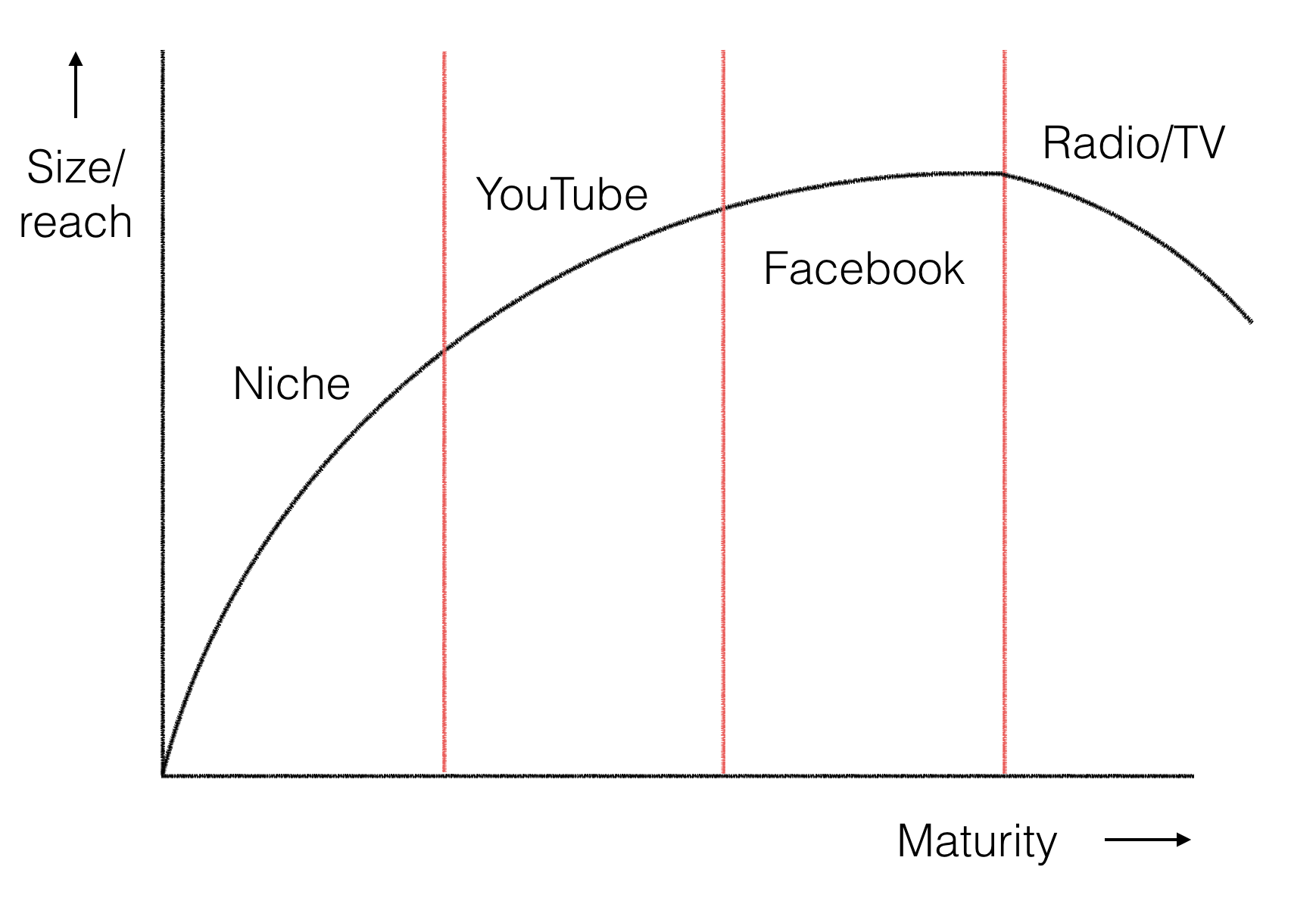

So, you’re an entrepreneur with a growth hacker mindset, and you feel you’ve checked the “compelling distribution hypothesis” box. How do you test your theory? Chen has a helpful model, called The Life Cycle of a Channel.

He says that the performance of any channel degrades over time (see his essay on The Law of Shitty Clickthroughs which looks at why successful marketing strategies become less effective at scale). Early on in a channel’s life span, when it’s smaller and has less reach, it’s likely to have high responsiveness rates as users try it out for the first time. The “niche” stage is the perfect time for a startup to get involved: “If you can figure out that you have this product that especially fits [with a particular channel] — you know Instagram really well, or Snapchat really well — magical things can happen.”

Chen warns that as channels get more and more mature, they reach a point where “only the big companies can really make [them] perform.” Once you’ve identified a nascent channel that might work with your product, you need to run a quick, light lift test to measure product/channel fit, such as through a partnership or a small integration.

“What’s the minimum network size you need to make something work?”

Another key question Chen says startups should ask themselves is about the “minimum network size” needed for a product to work. For a texting app like Whatsapp, that number might be as small as two. A sender and a recipient. But a dating app like Tinder needs more people in its network to be useful. The principle of network effects applies. Chen says settling on your company’s minimum network size, and making it as small as possible, has a lot to do with the category of product you’re trying to build — a publishing app might have a higher bar than a communication app, for example.

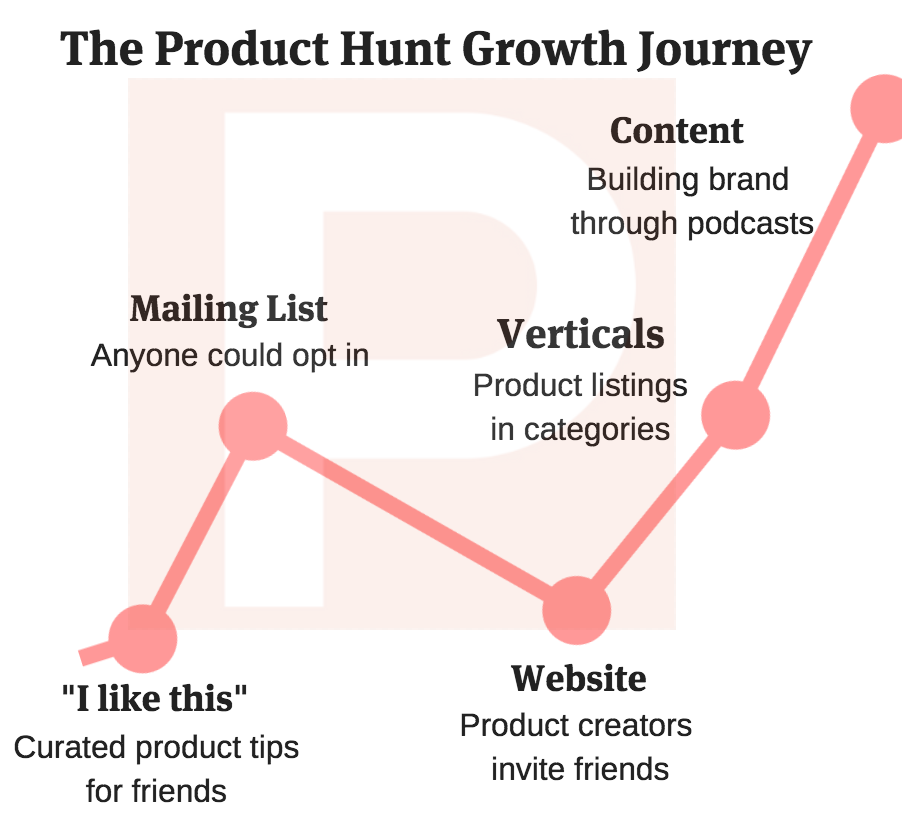

He uses the example of Product Hunt, a startup in which he was an early investor. It started out with Ryan Hoover curating products he liked and emailing them to his friends. Minimum network size? About 5. But then he decided to scale and build a mailing list, and then a website around the mailing list, and Product Hunt was born. It’s since diversified into all sorts of verticals, as well as its own content creation, including podcasts and live chats with notable founders. Chen points out that the go-to-market growth strategy was not the same one as Hoover used through each phase of the company’s development: personal relationships to word-of-mouth to SEO and press, to brand-building through content.

“You’re always trying to figure out how to scale yourself.”

As well as being Uber’s growth maven, Chen has also established a strong personal brand. For the best part of ten years, he’s been a prolific essayist, and used to publish a blog post a week.“The way I ultimately justified it was to think, ‘instead of going to networking events, imagine if you just took all that time and you just invested that in writing?’”, he says. “Some of my happiest moments with my blog have been cases where I’ve met somebody for the first time and they feel like they know me because they’ve been reading my work for four years.” Then he took things a step further and started The Backstory, a Product Hunt-style discussion forum for all things product + growth. He hosts the content but doesn’t have to create it himself — thus scaling his impact. An Andrew Chen growth hack.

For more pearls of wisdom from Andrew Chen, the story of why his startup didn’t go the distance, and a teeny weeny bit on Uber’s quest for world domination, check out our video:

Want more of Andrew Chen? Check out his blog, or sign up for The Backstory.

The Drunken Walk is a series of live fireside chats, blog posts, and podcasts (coming soon!) from Matter Ventures, the world’s only independent startup accelerator for media entrepreneurs. We dive into the personal stories of founders, experts, and innovators in media to uncover the moments in their careers that changed everything. Our goal is to inspire and empower the next generation of media entrepreneurs to get from A to B without a map.