“If a million people saw this story, would it make the world a better place?”

In February, 2011, 19 year-old University of Iowa student, Zach Wahls, spoke before a Iowa House of Representatives public forum to oppose an anti-marriage-equality measure. Later that year, an intern at MoveOn, a progressive advocacy organization, suggested sharing the video of his speech on its site. One catchy headline — “Two Lesbians Raised A Baby And This Is What They Got” — and a million views later, it had officially gone viral, and sown the seeds of a content curation startup that would later be spun out into Upworthy.

Upworthy never set out to do good news. Its co-founders, Peter Koechley and Eli Pariser, simply wanted to bring greater visibility to “the stories we need to make society work.” They say they’re not even particularly positive people. “We’re hopeful. But I don’t think anyone who knows us thinks we’re sunny,” Koechley recently told our New York City-based entrepreneurs. During his “The Drunken Walk”* fireside chat with Matter Managing Partner, Corey Ford, he illustrated the pivotal moments of Upworthy’s journey over the past 4 and a half years.

Two men made a startup and this is what they got.

Like many loving parents, Eli Pariser and Peter Koechley struggled to name their offspring. Once upon a time, Upworthy was to have been hot.com. On one startup funding platform, hot.com is listed as “a viral media site that fills the void left by Huffington Post, makes progressivism fun again, and propels important messages to millions.” Pariser and Koechley, both previously of MoveOn, are named as co-founders. Fortunately for them, they moved on from a company name that sounded like a porn site, and a domain name that would have cost them up to 40% of their seed funding.

Then Upworthy was to have been Upriser. The duo acquired all the relevant URLs, apart from the .com which was due to come up for auction. At the last minute they were outbid by “a very intense individual” (who owns the site to this day) with whom negotiations proved futile. Koechley and Pariser rushed to find an alternative company name in time for their launch, something similar to Upriser so that they could reuse the branding and website they’d already developed. “Upworthy” came to Pariser while on his morning jog (it was roughly the fifth such “In Search of Inspiration” jog he’d been on). Other bolts of brilliance from that era included “Propelify,” “Upbam”, “Feverly”, and “Uppable.” But all the Upworthy domain names were theirs for the taking.

“Our drunken walk was this period of really not knowing what we were doing.”

Back in 2011, before they knew what Upworthy would be, let alone its name, Koechley and Pariser had noticed a problem: the top stories in traditional broadsheet newspapers just didn’t carry the same appeal online. “The shift from newspapers to news feeds was going to leave a lot of important stories behind because the stories that actually matter to society aren’t naturally shaped to be shareable,” says Koechley.

He had previously been Managing Editor at the satirical news website, The Onion, and co-created its parody newscast, the Onion News Network. Pariser was Executive Director at MoveOn, a strong analytical thinker, and had written a book, The Filter Bubble, about the effect of algorithms on our media consumption habits. The pair knew email and social media well, and were great political organizers. Upworthy was a way to synthesize all those strengths and interests — at this stage they were largely designing for themselves. But one initial hypothesis proved to be flawed: comedy was not the right conduit for getting “important” content to as wide an audience as possible: “We found out that comedy is actually not that shareable. Even though people share funny things, comedy selects for a group of people who [like the same thing].”

Koechley is candid about knowing the problem statement, but being clueless as to the solution. At first the team experimented with crowdsourcing, a domain they knew well from political canvassing. They had a swarm of volunteer editors who would suggest a YouTube video or an article to curate, and built an editing tool for them. But it took Zach Wahls and a clickbait-y headline to crack the formula. He racked up several million views in several days, and the company shifted to curating “earnest,” emotive videos that could inspire change.

That fall, realizing they were on to something with massive potential, Koechley and Pariser decided that they needed to separate their skunkworks team from the non-profit, a decision that kind of crept up on them. They raised $2m fueled by, Koechley says, “white male privilege” and evidence that they’d “reverse-engineered virality and built the machine to create it.” The following year they started from scratch, having left most of their collaborators behind at MoveOn.

“We both had the sense that we were getting very lucky.”

The Upworthy recipe for success was simple:

curate great videos that are not getting the audience they deserve,

package them so people understand why they should care about them,

add them to Facebook.

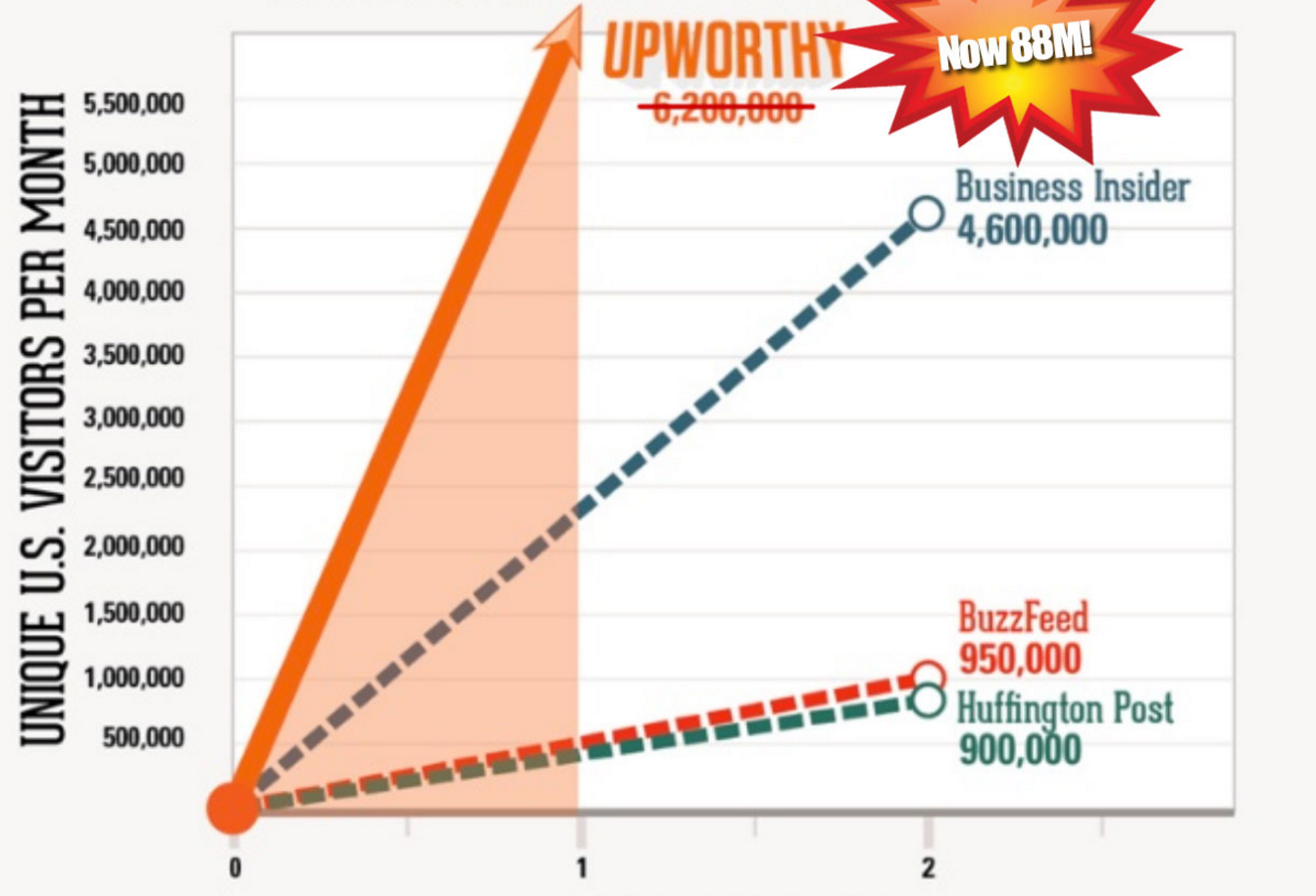

It worked better than the duo could have imagined in their wildest dreams: “We were lucky enough to have a crazy rocket ship, up-and-to-the-right thing that you want as a startup. We had a slightly different problem, which a good problem to have, kind of racing to keep up with ourselves. Each month was better than the last.” One month they reached 87 million people, and wrote a blog post about it. Koechley wishes their public face had been more pragmatic at the time: “In retrospect it would have been better to speak a little more openly and say, we’re riding a wave here. We’re doing some smart things to ride it well. But the future is uncertain, as always.”

Upworthy didn’t, of course, keep on moving at that breakneck speed. Years 3 and 4 were a much more typical start up experience, with a bunch of highs intermingled with plenty of lows. By mid-2014, the “clickbait with a conscience” formula wasn’t working as well as it used to (thanks to Facebook’s clickbait squashing). Upworthy started to shift from curation to creation, following the “Netflix model” (from licensed content to original content) that the co-founders had had in mind since the early days. In 2015, they officially renounced clickbait, announced a shift towards original content, and hired Amy O’Leary from The New York Times (formerly NPR) as Chief Story Officer to oversee the transition.

When Upworthy was young, Koechley says they capitalized on the fact they were newbies who were willing to take risks because they didn’t know the established way to do things. But now they deeply value experience when it comes to hiring. They try to bring in “accelerants,” people who are “better” than they are at what they do, and they don’t play games about it: “Rather than trying to act like the cool one who doesn’t call the next day, we are like, yes, we want you. We think you are great.”

Under the leadership of O’Leary and digital video veteran, Croi McNamara, Upworthy restructured its staff earlier this year to direct more resources towards a 9-people original video team. They still license and share a lot of viral content from all over the web, but the site’s original videos perform, on average, three times better than the curated stuff. Over the last 18 months, monthly views have gone from 4 million to 330 million.

It’s the time for lots and lots of experiments, says Koechley, who now feels like he’s in the company driving seat as opposed to playing catch up. “We’re doing a lot more failing than we’ve ever done before. Is that an improvement?,” he jokes. “We’re at a time where we’re trying new things, branching out in different directions. Fewer of them are working.” But that’s a good thing, right?

The Drunken Walk is a series of live fireside chats, blog posts, and podcasts (coming soon!) from Matter Ventures, the world’s only independent startup accelerator for media entrepreneurs. We dive into the personal stories of founders, experts, and innovators in media to uncover the moments in their careers that changed everything. Our goal is to inspire and empower the next generation of media entrepreneurs to get from A to B without a map.