Is teaching girls jewelry design to get them excited about 3D printing sexist or smart?

Top highlight

As a senior in college, I wrote my thesis on the artwork of Kara Walker. Her silhouettes paint pictures of our own psyches. Intricate black and white outlines are initially empty and ambiguous, until the viewer’s eye begins to trace along the void, projecting their own pre-conceived notions into the blank space — playing out like a Rorschach test of one’s own inner monologue about race, gender and history.

Through discussions of gender roles as both a female founder and as a founder of a KiraKira, a company devoted to female education in mechanical engineering and 3D modeling, I have encountered many stereotypes and, as I learned years ago from staring into Walker’s work, many opportunities for subversion. Walker’s artwork serves here as a visual and conceptual framework for this exploration of art, society and gender.

I consider questions of my identity as a woman: both through my own self-perception as well as external recognition. How do I see myself as a woman-artist, woman-teacher, woman-founder, and how do I others see me? Now that gender is central to our work, I consider: how do our users — middle school and high school girls — see themselves now and how can we empower them to perceive limitless career choices?

At age 6, what careers do most girls aspire to and how does this change over secondary and high school? We know that in middle school 62% of girls are on par with boys and proficient in math and science, but by the time they are entering high school this percentage plummets to 21% (*US Dept. Education 2014).

We are interested in testing various modes of reaching these girls and also being self-reflective. Through engaging girls in learning transferrable engineering skills with online jewelry design lessons, are we perpetuating sexist stereotypes? Or are we using jewelry merely as a construct of something quintessentially ‘girly’ and a gateway that allows us to reach an audience that might not otherwise engage in learning engineering concepts and software? This question of sexism vs. subversion lingers and is something we explore continuously.

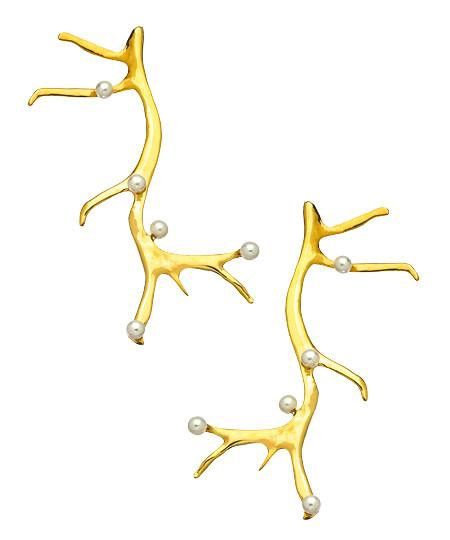

After studying gender and race in modern art at Brown, I began exploring silhouettes through jewelry design and studied 3D modeling at RISD. I created 2D silhouettes through empty baroque cameos and and oxidized inverted antlers. Soon most of my pieces were made with 3D modeling software: Autodesk, Rhino, Solidworks, and Delcam. Each program offered different opportunities. I wished I had been given the opportunity to study these programs at an earlier age. 3D modeling opened up a new world of creative freedom. I wanted to share this with others but was not sure how to go about this other than to be a teacher and to mentor aspiring designers in CAD.

Through an incubator at Darden (UVA’s MBA program) a couple of years ago, I began working with UVA students who mostly were interested in fashion and design. When they realized that I 3D modeled all of my designs, they became interested in learning these programs too. We began working with UVA’s engineering department and the (female) students started taking introductory classes to Solidworks. I saw their interest in learning crescendo in my studio and fade in the mech lab.

Within a day or two, most of the students lost interest. The creative process that initially ignited them was not illustrated in the current curriculum offered. Our interns did not want to learn how to make wrenches or auto-parts or wind turbines through a step by step process. They wanted to learn the tools to be artists and, more simply, to get started making things. They wanted to learn how to be creative.

Together with my co-founder, Malena Southworth, we began testing ways to engage these girls and to build our team. Malena, an amazing artist and designer and mother of three young children, brought with her an incredible aesthetic and a passion for female education and teaching. Couldn’t we teach comparable concepts to class constructing a wrench instead through a class constructing a hinged cuff bracelet?

How best do we reach this female audience? Thinking about gender, specifically redefining female identity in relation to careers in engineering, I think it’s important to consider our need/desire to suppress what is frowned upon as stereotypically female. Can women not balance ultra-feminine and stereotypically masculine qualities at once? Why do these feminine qualities need to be censored?

Censorship is also central to Walker’s work and something that has impacted the way I view gender. We can highlight the deficiency: girls are not (statistically) engineers, only 7% of mechanical engineers are female. In this vein, perhaps more women should learn to enjoy making wrenches as much as men. Alternately, we can highlight to the extreme (albeit absurd!) an age-old stereotype: that women like jewelry.

We began building the concept of KiraKira and started working with UVA engineering grads to teach transferrable skills through online jewelry design lessons. Each class begins with a focus on the creative process and ideation, sketching designs and troubleshooting how to make this concept a reality. Each class also introduces the face of a new (typically female) teacher and role model: an engineer, a microbiologist, an artist, a graphic designer, a high schooler. Their combined identities imbue our classes with diversity.

Through our classes and the KiraKira community of designers and learning, our goal is to quantify our social return on investment. We want to see girls who become a part of KiraKira become statistically more likely to pursue STEM curriculum and ultimately STEM careers. Through our work with Matter over the next 20 weeks, we want to develop our social network of female-focused learning, communication, empowerment and ultimately, we want to see the face of femininity in STEM change.

Something to note: KiraKira is not just for girls. We wants boys to also take our classes and teach our classes. We hope student-teachers sign up to make content beyond jewelry — something which has already begun. We asked our students what they wanted to make, and we listened. They wanted to make jewelry. They wanted to make iPhone cases. They wanted to make musical instruments. The stereotype was just our starting point.

Through KiraKira, students will be learning transferrable engineering and 3D modeling skills through fun student generated design lessons. Now our classes are becoming richer and more diverse as our students are dictating what they want to make, and in doing so, redefining the face of female engineers-designers-students-entrepreneurs-makers. KiraKira empowers young women to recast stereotypical definitions and to design their own futures.